Too often, policymakers disregard the human impact of management decisions in the name of conservation. Now, more than ever, we need equitable solutions for a thriving planet and people.

When we picture Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) I think it is fair to say that many of us imagine something akin to flourishing seagrass meadows, pristine coral reefs, or vibrant kelp forests, all brimming with an abundance of pelagic fish, marine mammals, bottom-dwelling invertebrates and the like. This paints a rather pretty picture of what marine life can look like when allowed to return to its natural, thriving state. What I don’t think that many of us picture are the unintended consequences MPAs can have on coastal communities who find themselves caught between conservation efforts and their own socioeconomic realities. These impacts can include the loss of livelihoods, strain on already marginalised communities and negative consequences for human well-being.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of this, I must make it clear that I am an environmentalist at heart and an ecologist by trade. My studies in marine biology have made me well aware of the benefits of MPAs for marine life, particularly in increasing the biodiversity and abundance of protected species, which is of course, vitally important for a healthy, thriving ocean and planet. I don’t think that anyone is arguing against this. I do, however, want to create a slightly more nuanced debate. One where we can talk about healthy oceans and healthy communities not as two ends of a spectrum, but as one unified goal. My journey into the dark side (the social sciences) during my PhD has enlightened me to the complex challenges that protected areas pose for people and ultimately for the planet too. If thriving oceans are the goal, we need thriving coastal communities too.

What is an MPA?

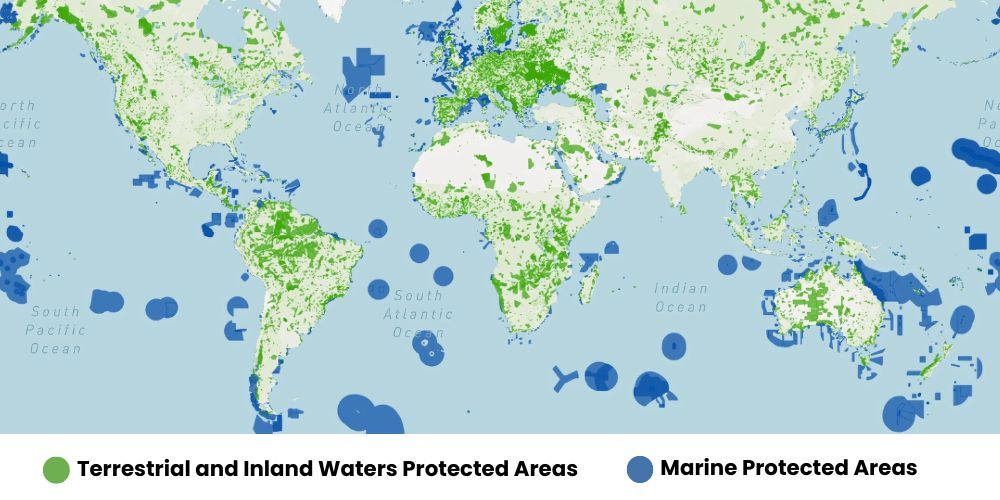

A Marine Protected Area is an umbrella term for all types of protected areas in the marine realm. Examples of MPAs include marine reserves, marine parks, special areas of conservation, marine conservation zones and no-take zones. We will not dive into the intricacies of each here. Importantly, they all share a similar goal of protecting at-risk and vulnerable ecosystems, habitats and species, through conserving and increasing biodiversity, improving productivity and re-establishing ecosystem integrity.

One of the earliest and most notable MPAs is the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP), established in 1975. Spanning 340,000 km², it remains one of the largest MPAs in the world. Today, over 12,000 MPAs exist globally, with most having been established in the past three decades. However, the scale of marine conservation efforts is set to increase dramatically following the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. This international initiative aims to protect at least 30% of the ocean by 2030 (“30×30”), a goal that raises critical questions about implementation and its consequences for coastal populations.

Winners and Losers

While it may be obvious that MPAs can have positive ecological benefits, they can also have positive outcomes for human health and wellbeing, including economic and social benefits for coastal communities. A paper published in Nature Sustainability reviewed 118 peer-reviewed articles that looked at outcomes related to marine protected areas on people. Findings showed that half of the documented well-being outcomes were positive and about one-third were negative. This may sound promising in favour of MPAs for human well-being. Yet, in my mind, 1/3 of 118 papers demonstrating negative consequences is pretty high, right? We are talking about people’s lives here. The paper goes on to admit that most studies focused on economic and governance aspects of well-being, leaving social, health, and cultural domains understudied. In simple terms, we don’t know what effects MPAs are having beyond financial implications because we haven’t bothered to study them. The review concludes that both human well-being and biodiversity conservation can be improved through marine protected areas, yet negative impacts commonly co-occur with benefits. While MPAs can enhance well-being in some cases—such as by providing alternative income sources through tourism or sustainable fishing zones—they often create disparities. For instance, an MPA might benefit one fishery that retains access to a buffer zone while simultaneously increasing costs for another fishery that is displaced.

Unintended Negative Consequences of MPAs

Coastal populations, small-scale fishers, and Indigenous groups—those most reliant on marine resources—often bear the brunt of conservation-driven restrictions. These communities face challenges such as job loss, restricted access to traditional fishing grounds, increased competition for resources, and heightened conflicts over ocean space. These negative effects tend to be more pronounced in the short term because the benefits of ecosystem recovery, such as increased fish catches and higher incomes, take time to materialize.

A commentary published in One Earth poses two key challenges for human well-being outcomes in marine protected areas. First, human well-being is often poorly defined and measured using limited indicators like income, catch size, or catch per unit effort. However, well-being is a complex, multi-dimensional concept that varies among individuals and communities. Factors such as age, culture, ethnicity, gender, and roles within a specific fishery all influence how people experience well-being. If these diverse perspectives are not considered, the full impact of MPAs may be overlooked. For instance, while an MPA in Zanzibar benefited tourism businesses, it also displaced female seaweed farmers who had no say in the decision-making process.

The second challenge is that research on the well-being effects of MPAs has primarily been conducted retrospectively. While studying past impacts helps improve our understanding and adaptive management strategies, less focus has been placed on predicting future consequences of proposed MPAs. Anticipating these effects is crucial so that those affected can fully understand the implications and participate in decisions regarding MPA implementation and management. This includes finding ways to mitigate potential negative impacts.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework emphasises a human-rights-based approach, requiring the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous communities, small-scale fishers, and other stakeholders. This means that possible well-being impacts should be transparently discussed before an MPA is established. Yet, such considerations are rarely incorporated into MPA planning. Additionally, little attention is given to whether affected communities can endure the short-term challenges of MPA implementation while waiting for long-term benefits—or whether those benefits ultimately justify the initial hardships.

A Call for a More Inclusive Approach

MPAs are a critical tool for marine conservation, but their success should not be measured solely by ecological gains. A truly sustainable approach must account for the people who rely on these marine spaces for survival. As we move toward the 30×30 target, it is imperative to ensure that conservation policies are designed with, rather than imposed upon, affected communities. By integrating ecological, social, and economic considerations, we must endeavor to create marine protection strategies that support both thriving oceans and thriving human populations.