Today’s post is a little less human-focused and a little more ethics-centered. Here, we will discuss the use of Artificial Intelligence to solve today’s environmental problems, discuss ‘whale accents’ and answer some intriguing ethical debates, such as: Do whales have privacy rights? Read on to find out.

Humpbacks at Home

The waves are dancing today. They roll and loll forward, surging to the beach, speckled with sunlight. Unlike the grey, unmoving mass of yesterday. The ocean has undergone an overnight transformation, courtesy of the first bright, clear day of a foggy February. Looking out to the horizon from my perch upon the hill—a rather steep section of the South West Coast Path—I stare patiently at the endless expanse of glistening blue. A Humpback Whale has been spotted circling the headland at Watergate Bay, just minutes from my home in North Cornwall, and I am determined to catch a glimpse.

Field Diaries is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I wait, occasionally chatting with passersby and other eager hopefuls who should also not be at the beach at 3 p.m. on a Wednesday.

An hour later, I see something. To the left of the craggy headland, a black fluke briefly pushes out of the water, leaving a whirl of bubbles in its wake. I never see it breach but catch several glimpses of its dorsal fin and fluke as it rolls up and down the water column, unaware of its many spectators.

A Brief History of Whaling

I have been lucky enough to witness humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the wild twice. The first time was in Iceland; the second, the encounter above. Each time, I have been overcome by emotion, of awe and wonder at these incredible ocean giants. It is difficult to imagine a world in which these creatures no longer exist but that was almost a reality had it not been for the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982.

Early whaling, practiced by Indigenous communities such as the Inuit, Ainu, and Basques, was deeply embedded in social and cultural traditions. These groups developed sustainable hunting methods that ensured long-term resource availability. However, with the expansion of European maritime powers in the 17th and 18th centuries, whaling became a significant commercial enterprise. The demand for whale oil, particularly for lighting and industrial lubrication, drove an era of aggressive exploitation. Whaling peaked in the 20th century and many species of whales were hunted close to extinction.

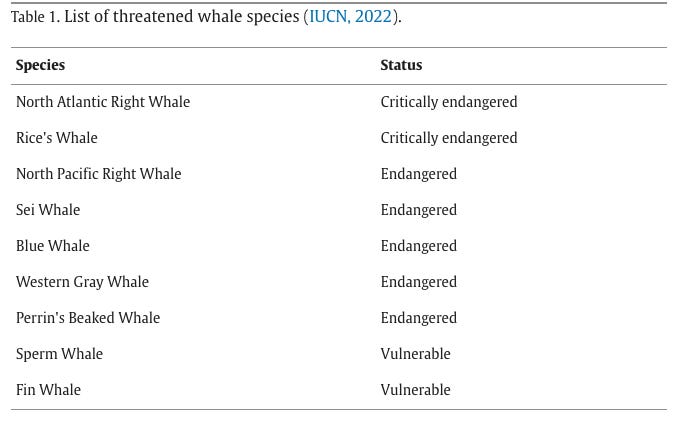

The International Whaling Commission was created in 1946 to limit whaling globally and promote the recovery of whale populations. It took until 1982 for commercial whaling to be prohibited, though it is still permitted in some nations, namely Japan and Norway. While the number of whales still hunted is relatively low compared to before the whaling moratorium, many species are still listed as at risk of extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Ryan & Bosset, 2024).

Whales are an incredibly important keystone species and their conservation is vital for the health of our oceans and, thus, our planet. New and emerging technologies have opened doors for more abstract methods of conservation to meet today’s rising challenges. One such approach is the use of artificial intelligence to decipher whale vocalisations, providing new insights and recommendations for their protection. This discussion explores a recently published paper that highlights the ethical challenges in using AI to decode whale vocalisation. (Ryan & Bosset, 2024).

Discoveries in Whale Vocalisation Using AI

Whales are highly social mammals that exhibit complex group decision-making and an intricate communication system. Research has shown that whales communicate using a complex system of clicks, whistles, pulsed calls, and songs that vary between species, within subpopulations of the same species, and across geographical regions.

New research published in Nature Communications suggests that whale communication is even more complex than previously thought. Project CETI, a nonprofit focused on using AI to understand whales, partnered with scientists from MIT to identify structure in the communication of Sperm Whales. Sperm Whales are incredibly social animals that communicate using patterns of clicks known as codas. Scientists already know that some of these codas help whales recognize each other, but much about their communication system remains a mystery.

The research employed several AI-driven methods to decode the Sperm Whale coda and revealed two key findings about their communication:

- Whale “accents” and style matter — Just like humans change their tone or add emphasis when speaking, Sperm Whales modify their clicks in subtle ways. These adjustments, known as rubato (changes in timing) and ornamentation (extra variations in sound), are not random; they are consistently used and even imitated by other whales.

- Whale clicks follow a complex coding system — By combining rubato and ornamentation with two other fixed features—rhythm (how clicks are spaced) and tempo (how fast they are played)—whales can create a much larger variety of codas than previously thought. This means their communication is far more expressive and structured than scientists once believed.

These findings suggest that sperm whales have a sophisticated, flexible way of communicating and that their “language” may be much richer than we imagined. However, much work is still needed to understand what different codas represent. A notable challenge in uncovering further mysteries of sperm whale communication is that different Sperm Whale pods have different sets of codas and juvenile whales communicate differently to their parents, thus, we are still a long way from understanding many complex aspects of whale communication.

Using AI to Speak Whale: The Ethical Considerations

While some challenges to deciphering whale communication are scientific, there are also potential ethical implications that require serious consideration.

The Risk of Anthropomorphism

One primary concern in using AI to analyse whale vocalisations is the risk of anthropomorphism—assigning human-like qualities to non-human animals. While AI can help identify patterns in whale communication, there is a danger in interpreting these patterns through a human lens, potentially resulting in misleading conclusions. In the English language, “moon” and “sky” relate to each other the same way as the French words “lune” and “ciel” do. Jacob Andreas, a natural language processing expert at MIT, explains: “With whales, the big question is whether any of this stuff is even present. Are there minimal units inside this communication system that behave like language, and are there rules for putting them together?” Scientists studying whale vocalisations must remain cautious and avoid forcing human linguistic structures onto whale communication.

Do Whales Have Privacy Rights?

It may seem strange to consider eavesdropping on whales an ethical debate, but several researchers argue that animals, like humans, deserve a right to privacy. While there is little evidence that recording whale vocalisations causes harm, the potential impact of AI-generated sounds on whale social structures remains uncertain. If scientists decide to go one step further and communicate with whales using AI-generated sounds, there is uncertainty about how this might affect their social structures, navigation abilities, and well-being. The ethical issue here is the possibility of interfering with a species’ natural way of life without fully understanding the consequences. As the research suggests, until we have more clarity on these impacts, such applications should be approached with caution

AI as a Conservation Tool, Not a Panacea

Technological solutionism—the belief that technology alone can solve complex problems—is another challenge. While AI is a valuable tool for studying whale communication, it is not a substitute for broader conservation efforts such as reducing ship strikes, preventing entanglement in fishing nets, and increasing public awareness. AI should be viewed as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, these conservation strategies.

Conclusion

The intersection of artificial intelligence and marine biology presents exciting possibilities for understanding whale communication. However, as we delve deeper into these studies, we must remain aware of the ethical implications. AI offers a powerful tool for decoding whale vocalisations, but we must ensure that our interpretations are scientifically sound and that our efforts do not interfere with the natural behaviors of these majestic creatures. Conservation must remain a holistic endeavor, combining technological advancements with traditional efforts to protect whales and their habitats.